Written by Sara K. Lyle, DVM, MS, PhD (LSU SVM 2008), DACT Assistant Professor of Theriogenology

Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences

LSU School of Veterinary Medicine

Overview

After expending considerable time in establishing pregnancy in the sub-fertile mare, it is imperative that she be adequately monitored to detect complications in the later part of gestation. The most likely complication to arise during the last third of gestation in the sub-fertile mare would be placentitis (infection of the placenta). Timely identification of placentitis is crucial for multi-modal therapy to be successful.

Most cases of placentitis occur because bacteria gain access to the placenta movement through the cervix. Clinical signs include premature udder development and lactation (Fig. 1), vulvar discharge (Fig. 2), and premature delivery or stillbirth. Abortions can occur from 75 days to term, although the majority of clinical cases are noticed during the third trimester. These premonitory signs are more common with fungal infections than with bacterial infections. A special type of placentitis is nocardioform placentitis, seen most commonly in central Kentucky. With this type of placentitis, discharge from the vulva is very uncommon, but mares will have premature udder development.

Diagnostics

Ultrasonography is a key diagnostic modality for diagnosing disturbances of the fetus and uterus. Evaluations are made both transrectally and transabdmonially, and are best performed when the mare is restrained in stocks in a quiet environment. Mare agitation or anxiety can elevate fetal heart rate, which could be interpreted erroneously as fetal stress. Sedation is also to be avoided if possible, due to the associated lowering of the fetal heart rate. Hormonal profiling can provide crucial information and is complimentary to the information gained by ultrasonography. Other modalities that can be used include sampling of fetal fluids, and echocardiography.

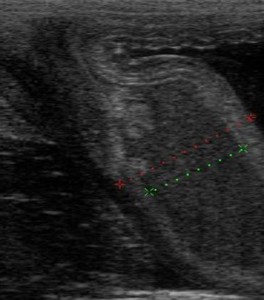

Transrectal Ultrasonography –An increase in the combined thickness of the uterus and placenta (CTUP; Fig. 3), especially with concurrent accumulation of fluid between these layers, is characteristic of placentitis. Edema of the placenta at term is normal and simply indicates impending delivery. Edema of the chorioallantois, or a discernible difference in the echogenicity of the uterine wall and the chorioallantois at other times should be considered as an indicator of potential premature delivery. Fetal presentation and positioning is easily confirmed by identifying the presence (normal) or absence (breech) of the fetal eye adjacent to the maternal pelvis.

Figure 1. Ultrasound image of a mare with placentitis, with fluid accumulation (green line) between the uterus and placenta.

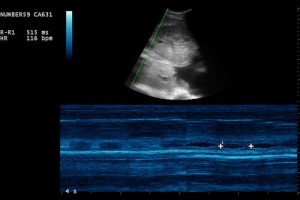

Transabdominal Ultrasonography – Transabdominal ultrasonography is useful for assessing fetal heart rate (FHR; Fig. 4), fetal activity, fetal presentation and position, character and depth of fetal fluids, as well as in cases of placentitis not due to ascension through cervix (e.g., nocardioform placentitis or blood-borne infections).

Figure 2. Echocardiography (ultrasound) of the fetal heart.

Hormonal profiling – Several hormones in the maternal circulation may be useful to monitor during high risk pregnancies. Total progestins (“progesterone”) are commonly measured in pregnant mares, although single samples probably are not as informative as serial samples. Total maternal plasma progestins are low until the last 2-3 weeks of gestation, climb substantially, and then fall abruptly within 24 hours of parturition. Increases in progestins prior to day 315 may be seen with placentitis; abrupt declines in progestins are associated with severe fetal compromise and impending abortion.

Therapeutics for the High Risk Pregnancy

The exact list of therapeutic agents needed for an individual mare will vary depending on the reason for the high risk status. However, a few agents are commonly used in many high risk mares: altrenogest (Regumate®, flunixin meglumine, pentoxifylline, and antibiotics. Firocoxib (Equioxx®) is useful when prolonged non-steroid anti-inflammatory drug use is indicated. Vulvar discharges from mares with suspected placentitis are typically contaminated with commensal microflora making isolation of the causative organism difficult. Broad-spectrum antibiotics (trimethoprim sulfa, ceftiofur, or penicillin and gentamicin) are indicated in these instances.

Conclusions

Timely identification of abnormalities during the last trimester of the sub-fertile mare is crucial to achieve the desirable outcome of a healthy neonate. The success of multi-modal therapy for placentitis hinges on early recognition of infection. Unfortunately the clinical symptoms of placentitis are not consistent, but a combination of serial ultrasonography and maternal hormonal profiling may allow the earliest identification of mares with a compromised pregnancy. Sub-fertile mares, or those with a history of previous ascending placentitis, should have serial examinations beginning no later than the start of the last trimester. In some cases monitoring from mid-gestation onward would be prudent. Further research on bio-markers for identifying infection of the allantoic fluid will aid in improving outcomes of cases with placentitis.