Written by Barbara Newtown

Original Publish Date June 2013

I interviewed Talmadge Green while he was on the road between his ranch in Sandy Hook, in south Mississippi, and a big futurity in Fort Smith, AR. He said he doesn’t mind a long drive: “Prize money makes for easy driving. On the way up, you’re thinking about winning, and on the way back you hope you have won a lot!” His trailer was full of four-year-old horses going to a barrel-racing futurity. He explained the difference between futurities, derbies, and open competitions: A futurity is for 4-yr-olds, a derby is for 5 and 6-yr-olds, and open is for any age horse. He assured me that there is no problem putting a four-year-old into a barrel competition; their legs can take it. Most Quarter Horse knees are strong enough for hard work by age 3. Green flat-races Quarter Horses as young as two, but he X-rays their legs to make sure their knee joints have closed. Green also protects his young barrel horses’ legs by attending no more than ten events in twelve months. “I want them to finish the year really sound legwise, but also sound in their minds, so they can be a good, good horse.”

I interviewed Talmadge Green while he was on the road between his ranch in Sandy Hook, in south Mississippi, and a big futurity in Fort Smith, AR. He said he doesn’t mind a long drive: “Prize money makes for easy driving. On the way up, you’re thinking about winning, and on the way back you hope you have won a lot!” His trailer was full of four-year-old horses going to a barrel-racing futurity. He explained the difference between futurities, derbies, and open competitions: A futurity is for 4-yr-olds, a derby is for 5 and 6-yr-olds, and open is for any age horse. He assured me that there is no problem putting a four-year-old into a barrel competition; their legs can take it. Most Quarter Horse knees are strong enough for hard work by age 3. Green flat-races Quarter Horses as young as two, but he X-rays their legs to make sure their knee joints have closed. Green also protects his young barrel horses’ legs by attending no more than ten events in twelve months. “I want them to finish the year really sound legwise, but also sound in their minds, so they can be a good, good horse.”

Green’s goal is to help others achieve the success he has already experienced. “I’ve won everything that you can win–seven world championships, seven-time winning trainer, and over three million in prizes.” Now he produces horses that are ready for women to use on the pro circuit, or are ready for kids who want to do the big barrel races. “A good horse can win $100,000 to $200,000 during the year. You can sell it for more than that, if it’s broke correctly and a kid can get on it.”

“I want the horse really broke before we ever go to running barrels on him,” said Green. “The reason is, if you get into a little bit of trouble during your run, if he’s broke, you can help yourself out. If he’s not, you’re just going to be along for the ride.” A lot of Green’s kids do competitions over three days, and only a well-broke horse will maintain the consistency required to win the big money.

Green said, “I travel so much; I do schools in Brazil, Australia, and all over this country.” Since horses need consistency during the breaking period, he employs other trainers at his ranch to get the horses started. However, he takes over near the end of the training and puts on the finishing touches.

I asked him about how much conditioning a barrel horse needs. He said, “My philosophy is, I love steak, but if I start on Monday and eat it every day, it doesn’t taste as good on Saturday.” He puts his horses on a freestyle exerciser two or three times a week. (In a freestyle, the horses on a hot walker are separated by solid panels and don’t have to be tied.) They trot for twenty minutes each way, and then walk for ten each way. Once a week the older horses are fitted with bitting rigs for the freestyle work. Green explained that the bitting rig is adjusted loosely, “not like for an equitation horse,” and the bit is a mild snaffle, so that the rig “just softens them up a little in their face.”

Experienced horses don’t work on barrels at all during the week unless they have specific issues. Once they get to the show, Green “freshens them up a bit.” The younger horses do get some barrel training between shows. “Since the barrel horses are doing sprints, I don’t see them having to be in shape like a Thoroughbred that’s running a mile and a quarter or a cross-country horse. But I do like to long-trot them a total of three miles a week; it helps their stifles, and avoids bleeding problems.”

Green mentioned that the students he has that come from a three-day-eventing background (dressage, cross-country, and stadium) have excellent hand position. They keep their hands low and just forward of the saddle. Olympic eventing champion Karen O’Connor calls this area the “dinner plate,” just over the withers. That’s the same position that Green teaches to his riders. “You get in trouble in barrel racing when your hands get far away from your body. You’re dealing in thousandths of a second. You might use your legs some, but the eye-hand connection is faster. When you go into that arena wide open, you only have so much time to react. I always tell the kids and the women, I want to put money in your pocket. When your hands are way out away from your body, you’re giving it to other people! It really relates to the women, because then they can shop more!”

Green said that he has always ridden in a cowboy hat, but more and more kids are wearing safety helmets, and that’s good. “Particularly in the last three years, I’ve seen some accidents where the safety helmet made a big difference.” He thinks there are more accidents than there used to be. “Some of it is the coaching, and some of it is that they think they’ve got to go all out.” He teaches that controlled speed “is what wins the championships and most of the money.” He stresses that he has won a lot, even though he doesn’t carry a crop and rarely uses his spurs. “I believe if a horse respects you, he’ll do everything you want. A lot of times, if you go to whipping a horse, you aren’t thinking about your hands or riding to your spot. The next thing you know, you’ve hit the barrel and blown off the back side.”

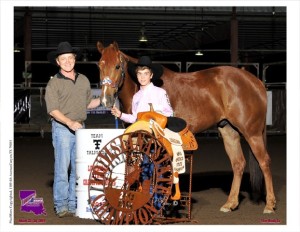

Allie and Max Chouest of Cutoff, LA, 12 and 11 years old, started riding barrels a year ago when they joined “Team Talmadge,” a group of kids that Green has been training for two or three years. One of Green’s clients had told the Chouests that Green had good horses for sale, and the family came to Green’s ranch and bought one, and ended up becoming his students. Now Allie and Max and their parents, Dino and Joan, enjoy the barrel-racing life: they’re building a second barn at their ranch, they haul in a trailer with living quarters, and they are learning the fine points of the sport from a fine trainer.

Green said that a year ago Allie wouldn’t go faster than a trot. “How are you going to barrel race if you won’t lope?” he asked her. Max was more of a daredevil, and three weeks after he started riding with Green he made the finals at Josie’s Junior World. “That cranked up Sister!” said Green. “She started getting competitive.” Allie and Max’s learning curve has been phenomenal: in the first two weeks of this May, for example, they earned $10,000. “Their dad gave me the chance to start them from the ground up,” said Green. “It’s been really neat to watch how fast they develop. But also we knew we had the means to find some of the best horses. Some people out there get kind of jealous, and say some things that shouldn’t be said. I tell them, I could go out and buy Jeff Gordon’s race car, but I’ve still got to drive it around the track and keep it from hitting the wall.”

Allie’s favorite horse is Buddy Rose, a sorrel. “I really love Buddy. He’s really fun and easy to ride.” Allie says he’s calm in the gate, and then goes fast…the perfect barrel horse. Max’s horse VF Sporty Design is the best money-maker. He’s a big-bodied horse who won over $150,000 for Green in the futurity division (he’s 11 years old now). Max is only 70 or 80 pounds; Green feels that in the next year or so as he grows he will become an even better partner for the horse (a “big” horse in barrel racing is 15.3). Allie and Max have expanded their string to four horses each for competition, and Allie’s mare Smash stays at their ranch full-time for trail riding. Green and the Chouests own a young stallion they are promoting named Hesa Cowboy Casanova, a son of Dash ta Fame, and a gorgeous golden palomino. Green pays attention to a horse’s breeding “to increase the odds.” He spoke highly of Dash ta Fame and Designer Red, sire of Max’s winning horse. (Designer Red is now in Brazil, but he’s still available through frozen semen.)

Green said, “I started riding barrels when I was nine, and I’ve been doing it professionally since 1985. I’ve worked, I’ve been around, and I’ve ‘done,’ but it’s remarkable what these kids have accomplished in a year’s time. They’re running with the best pros out there, and they’ve outrun me in some barrel races. Allie was at the PBR in Oklahoma City, where there were over 4,000 runs, and she ended up with the second fastest time, and made reserve champion. I teased her and told her a year ago she was so scared of competing that we practically had to lead her around. Max would have been third at the PBR, but he tipped over a barrel. Now, Tiger Woods was meant to play golf when the good Lord brought him into the world. Michael Jordan was meant to play basketball. These kids have some real natural ability.” And Green points out that Dino and Joan have raised them to be polite and respectful.

He is proud of all the kids he works with. “They work really hard, and they’ve got good parents.” He has students who come from as far away as Georgia and Ohio to attend his summer camp. They bring their competition horses, but during the week Green supplies the students with his own horses so that they can perfect their technique. The good horses only work on the weekends. “My philosophy has always been why waste a run when you aren’t going get nothing paid for, when you need it when they’re going to pay you the money?”

“When I was in the alley about to go in, I don’t know if I wasn’t smart enough to feel nerves, but I just never got nervous. Now, when I get the kids and adults I work with to the gate, it’s out of my hands, and I do get nervous! I feel like I could be a horse cribbing on wood, but I’m cribbing on bars.”

“When I was in the alley about to go in, I don’t know if I wasn’t smart enough to feel nerves, but I just never got nervous. Now, when I get the kids and adults I work with to the gate, it’s out of my hands, and I do get nervous! I feel like I could be a horse cribbing on wood, but I’m cribbing on bars.”

Green teaches his kids to be competitive, but he also teaches them manners. “It’s what I taught my son, who’s in college now. You be a polite and classy winner, because if you’re going to be cocky when you win, I’ll make sure you are cocky when you lose. The best thing is to win graceful and lose graceful. When you leave the arena, and people say ‘Nice run,” you say ‘Thank you, sir,’ or ‘Thank you, ma’am,’ because as fast as you got up there, you can fall to the other side way faster.”

Let’s let Allie Chouest have the last word: “We’re having a lot of fun! I want to thank Mr. Green and Megan and my parents.”