Written by Barbara Newtown

Original Publish Date: June 2014

I watch Glenn Delahoussaye, mounted on his little bald-faced paint Boss Hogg, as he gets ready to pony an eager young Thoroughbred around the 7/8 mile track at Evangeline Downs Training Center in Carencro, Louisiana. Boss Hogg, Glenn says, is named in honor of the corrupt county commissioner in The Dukes of Hazzard. Boss has seen it all during his career as a pony horse. Nothing bothers Boss—except plastic containers that crackle when stepped on.

I watch Glenn Delahoussaye, mounted on his little bald-faced paint Boss Hogg, as he gets ready to pony an eager young Thoroughbred around the 7/8 mile track at Evangeline Downs Training Center in Carencro, Louisiana. Boss Hogg, Glenn says, is named in honor of the corrupt county commissioner in The Dukes of Hazzard. Boss has seen it all during his career as a pony horse. Nothing bothers Boss—except plastic containers that crackle when stepped on.

“I have to keep an eye out for bottles on the ground,” says Glenn. He accepts Boss’ quirks and appreciates Boss’ strengths.

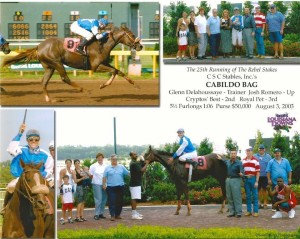

Glenn’s philosophy for training horses is flexible and draws from many traditions, but the most important tradition came from his father. Junius Delahoussaye gave his son two pieces of advice when Glenn announced that he wanted to be a race trainer. The first: “Always surround yourself with the best people.” The second: “Always race against worse horses.”

“My father was the most gifted person with a horse that I ever knew,” says Glenn. Junius had a sixth sense when it came to understanding a horse’s ways. “I have to work and study more, though. A horse’s fear can manifest itself in so many different behaviors. You have to figure out if the horse is afraid or just feeling good.”

Denise, Glenn’s wife, taught elementary school for twenty-five years, and Glenn taught drug abuse awareness classes in middle school for fourteen years. One thing he learned from Denise and from his own experience is that every child is different. “They don’t all respond to the same stimuli and the same discipline,” he says. “It’s up to the teacher to decide what works best, through trial and error. If you apply the mentality of the child to the horse, you will be successful. The difference is that a child can tell you when he is hurt or angry or lonely or tired, but the horse can’t. You have to study the animal and recognize when to push forward, and when to halt.”

Glenn snaps a leather lead onto the left bit ring of a lanky, dark brown Thoroughbred with a prominent nose. Jason, the jockey, keeps the big horse collected and curled, and he and Glenn hold the horse’s head next to Glenn’s right knee. The race horse stands about 17 hands and fizzes with energy, but Boss Hogg isn’t worried. He keeps a steady, straight canter while his companion bounces up and down as much as forward. Glen and Jason take their mounts to the outside rail and continue to the right, and stay well out of the way of the horses galloping and breezing to the left on the inside. After once around the oval, Glenn brings Boss back to a trot. They continue to the fence at the end of the straightaway, halt, and walk back to the exit from the track.

Even though Glenn and Boss and Jason kept the Thoroughbred to a collected canter, he is wet. Glenn says, “Once they get a certain amount of racing in them, they know. The aggressive ones don’t need to work hard to get wet when they go out on the track with the pony horse. This horse, he was never out of the bit. He got more out of his workout by being controlled. That’s exactly what I wanted.” Glenn won’t take the horse’s speed away by letting him “run wild” and do what he wants to do. He also doesn’t care if the racehorse swaps leads or canters with his hindquarters to the inside. “I wasn’t concerned about leads. I was concerned about containment. You don’t want him cantering sideways if you want to be proper, but I knew if I let him straighten up, raise his head, he’d be out of control. As long as I’ve got his head tucked behind my knee, he isn’t going anywhere. And he knows that.”

As we wait for Jason to bring out the next horse, Glenn shares some of Junius’ wisdom. “My daddy used to say, you can’t hurt a horse by breezing him—asking him for speed—but you can hurt a horse by breezing him without galloping him.” Glenn explains that training Thoroughbreds is not about speed, it’s about stamina. “Quarter Horses—now that’s about speed! The most a Quarter Horse will run is 220, 330, or 440 yards.”

Snarky Belle is a chestnut filly with a wide blaze. Jason takes her out alone onto the track. Glenn says that Snarky will be racing in four days over a short distance, because she is only two years old and not developed enough to have great stamina. “Short” for a Thoroughbred is 4 ½ furlongs; a furlong is an eighth of a mile, so Snarky will cover just over half a mile, which includes one turn. In her last race, which was her first outing, Glenn says she “raced kind of green.” When the horses broke from the gate, the horses on each side of Snarky broke fast and crossed in front of her, and “knocked her back.” Snarky got scared. “This time Jason is taking her counterclockwise, just like the last horse. We aren’t asking for speed. We want her to relax and stretch her legs a little, and save herself for the race.” Jason keeps her collected in the canter. “If he lets her go, she won’t have anything left on race day.” Glen explains that Snarky is fundamentally sound in her race training; she loads into the gate quietly, and she listens to her jockey. She just needs some confidence.

“Snarky has a position near the rail for her race coming up,” says Glenn. “She breaks fast from the gate. I’m hoping the rail and the horses to her right will create a lane and she will go forward. She will use her speed to take advantage of the lane. Geometrically, that’s the lane you want to control: the shortest way home is on the inside.”

Glenn tells me that there is one situation in which you do not want the starting position closest to the inside. Since the Kentucky Derby is a mile-and-a-quarter race on a mile-long track, the starting gate is set a quarter-mile back up the homestretch. (The public gets to see the horses go by twice, which is always a crowd-pleaser.) When twenty horses race in the Kentucky Derby, the first starting stall is set close to the inside rail so that there is room for the auxiliary gate on the outside. However, the horse waiting in the number-one position can see the curve of the inside rail just as it straightens for the home stretch. It’s an optical illusion: the lane seems to narrow right in front of the horse. It is possible that the illusion might cause a horse to back off just a fraction when breaking from the gate.

I ask Glenn: why run the Derby with that many horses? “Human greed,” he answers. It’s not a fair race when so many horses are trying to get to the rail—and the one horse that has it at the start may not be determined enough to grab it. “Trainers cry about the one hole, as well they should. It’s the kiss of death.” He adds, “The Derby is an albatross. Nowhere else in American racing will you see a twenty-horse field.”

We watch as Jason uses the situations that arise as he and Snarky travel around the course: he lets Snarky get overtaken by cantering horses that are also going counterclockwise, and he moves up close to horses that are cantering in front of her. Glenn and I can see that Snarky gets a little worried when she’s crowded. “She’s looking for a lane,” says Glenn. Jason moves her over to the outside rail, relaxes the pressure, and Snarky straightens into her lane, happy again.

Snarky didn’t need Boss Hogg to accompany her on the track, but she does need help going back to the barn. “Come on, baby,” says Glenn as he rides up to her and snaps on the lead. Jason cozies Snarky up to Boss for the walk home.

The last horse to practice on the track is Giacomo Sparkle, a tall, dark, handsome filly with no saddle on. “Boss and I will take her around the track without a rider, because she’s recovering from a soft tissue injury,” says Glenn. He keeps Giacomo to a trot, but it is such a gorgeous, reachy trot that Boss has to canter to keep up. As they come back from their 7/8 mile circuit, I hear Glenn saying, “Easy, Mama, easy, Mama.” They halt and stand for a moment before heading for the barn.

I compliment Glenn on how measured and quiet he and Jason (and Boss) are with their young racers. “Barns are a reflection of the people. You won’t hear loud noises or yelling here. I am very careful about who I have working for me. Now, you do have to be willing to pay good people. You have to go the extra mile.”

Back in the cool air of his office, Glenn explains that in England the tracks go in both directions, and they teach their horses to go both ways. Since all American racing goes to the left, Glenn trains his horses to “think left.” He doesn’t want the horses to see going to the right as an option. Only the jockey can make the decision to swing out—and make the horse’s race longer. Even the hot walkers go to the left.

In dressage, horses are trained to be as symmetrical as possible. The one-sidedness of racing seems wrong to me, and my face shows it. Glenn laughs and points out that racing is not constructed to create balanced mounts but to encourage wagering. Money rules, and the best trainers find a way to train that allows them stay in business.

“I don’t gamble,” Glenn says. “Most good trainers I know don’t gamble, because we gamble enough every day. Racing is a complicated sport.” At the heart of racing is the horse, whose body is not made to do what we ask it to do. “I get a lot of first-time owners; they’re sent to me because people know I’ll take care of them. I explain it to them this way: put your fingers around your lower leg. Now come outside and put your fingers around your horse’s cannon bone. It’s two times smaller than our ankle. And they have to carry over a thousand pounds on just four of those legs. Racing is man’s idea. Not God’s idea.”

Glenn says that raising the racing age from two to three is not an answer. “There’s a misconception that horses that race at age two will break down. Research has shown that horses that race at two have longer racing careers than those who start later. There has never been a horse who won the Kentucky Derby who did not start racing at two.” Glenn maintains that injuries occur not because of chronological age, but because of a change in stress. “When you get to the first change of stress in their training regime, whether it’s age two or age four, the same sort of injury will occur.” Glenn and I discuss the fates of the wonderful fillies Ruffian and Eight Belles, both of whom broke down during or just after races. Ruffian’s match race and Eight Belles’ Derby run exposed the fillies to the best colts in the nation, and the fillies gave everything.

Horses are individuals, not only mentally, but physically as well. For instance, Glenn’s concern for soundness makes him cautious about asking horses for speed before their knees are closed. “Chronological age and bone age are different. I’ve had some horses whose knees didn’t close until they were five years old, and I’ve had some whose knees were closed as yearlings.”

Glenn is amused by “numbers” people. “Racing is more speculative than the stock market. Venture capitalists come to me with all this historical data and I say, That’s amazing! But flesh and blood are different. You can’t use the same stimuli that you use in the financial world.”

Ideally, Glenn wants to take on a horse that hasn’t been started by anyone else. “I want my horses to trust. In order for them to perform at the highest level, they need to trust and not be afraid. If I have a horse from the beginning, I look for problems before they happen. I know their characters.” He again compares a horse to a child. “It’s just like understanding people. Some horses are claustrophobic, but we don’t call it that, we just say they’re crazy. Some horses don’t like to be alone. If you put them in a stall, they go bonkers. So put a little pony in there with them. Training horses is just like understanding people. My way is not the only way, but it has worked for generations. Would you give up on your child just because he’s having a bad day?”