Written by Barbara Newtown

Original Publish Date August 2012

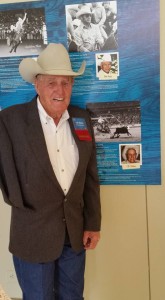

T. B. “Teaberry” Porter, age 85, of Leesville, Louisiana, is a longtime national rodeo star and tough as nails and leather. He had his arm amputated in March after a wrestling match with a bulldozer. By June, Porter was back at work on his 600 acre ranch, rising at 5 a.m. every morning, repairing equipment, baling hay, bush hogging pastures, and checking his 500 cows and calves.

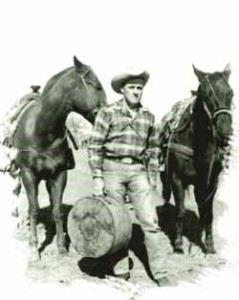

T. B. comes by his cowboy toughness naturally. His father raised stock for local rodeos, traded horses and cattle, and provided mules for working on the railroad. T. B. roped, rode, and trained animals not for sport or fun but because he was a real cowboy. By 1938 his father had acquired the big Leesville ranch, and T. B. was working right alongside him. By age 16 he was winning on the rodeo circuit, using skills he’d been learning since age 2, when he first sat on a horse.

“Daddy would trade horses for cows and cows for horses,” says T. B. “Texas ranchers would send their wore-out cow horses to Louisiana farmers for pulling plows.” But some of those horses were still pretty good, and found new careers with the Porters as rodeo talent. T. B.’s favorite horse was a black gelding named Hitler, a Thoroughbred out of King Ranch racing stock. Hitler had been traded to a Lake Charles rendering plant owner, but T. B. traded for him and turned him into a great roping horse and a straight, fast hazer for bulldogging. (His bulldogging partner rode a horse named Mussolini.) Most of the South Louisiana Quarter Horses that T. B. traded and trained over the years had a lot of Thoroughbred in them, much like the Appendix Quarter Horses of today.

In an interview with the Shreveport Journal in 1963, T. B. talked about training roping horses. “Roping horses are peculiar,” he said. “A horse that’s good for one fellow won’t be good for another roper.” T. B. said that it takes two years to make a good roping horse, starting with one that already has been working around cows. The horse must be fast, gentle, and must break quickly. However, “usually a roper looks for a good horse that’s already broken in and then makes a purchase of anywhere from $1500 to $3500.” In today’s dollars, that’s $10,000 to $25,000.

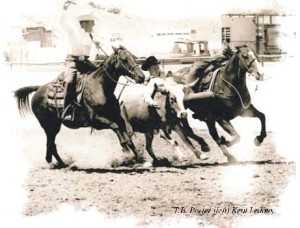

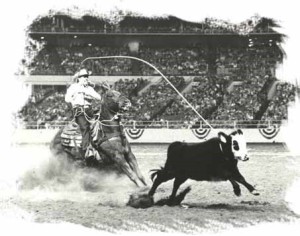

In T. B.’s heyday, calf roping was an individual sport. Team roping, with a “header” and a “heeler,” became part of the rodeo circuit about the time T. B. retired. Calves were heavier when T. B. was competing: 250-350 lbs., rather than 175-200 pounders we see today. Unlike today when most cowboys dismount to the right and run down the rope to flank the calf, T.B. and the cowboys from his era dismounted to the left and scurried along the rope to leg the calf due to the heavier weight. For that reason you can’t compare the speeds between then and now. T. B. says, “In those days 9 or 10 seconds would win you money.”

Besides calf roping, he specialized in bulldogging, both as steer wrestler and hazer. “I tried bull riding once,” says T. B. “But the bull bucked me off and stepped on my stomach, and I said that’s it.” His only injury in his rodeo career was some torn cartilage in his hand. “I wrestled a steer and he went down on the wrong side, on top of my hand.” Did he see a doctor? “Nope. It hurt for a while, though.” At age 2 T. B. had fallen off a porch and sustained a groin injury, which labeled him unfit for military service, but, apparently, not unfit for rodeoing.

In 1949, at 22, T. B. won the national calf roping championship at Madison Square Garden in New York City. He competed in 42 events over 28 days to secure the title. That was the first time any competitor had won on the first attempt, and the first time a Louisiana cowboy had won. He received a saddle, presented by Gene Autry, and $4000, comparable to about $40,000 today. He called his parents after the awards ceremony and said, “I just had to win” because he was the only cowboy from Louisiana. T. B. and Cindy, a bay mare, and Sunshine, a sorrel gelding, had driven from Leesville to NYC via Hope, Arkansas, where they picked up T. B.’s cowboy friend Ray Wharton. They drove mostly at night, “because we had no AC in those days.” T.B. pulled his homemade, fenderless trailer with a black, two-door 1948 Pontiac. Was he awed by New York? “I’d been to New Orleans and Dallas and Fort Worth and places like that, so it wasn’t that much of a deal. It was just another trip.” But he mentioned going up the Empire State Building and the Statue of Liberty, visiting the Natural History Museum, getting to steer the Staten Island Ferry, riding his horse down Broadway in the rodeo parade, and giving autographs to children in hospitals.

T.B. competed and won in rodeos all over the U. S., from Massachusetts to California, but most of his showing took place in Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas, and Missouri. He has won awards such as calf roping champion at the 1949 18th World Rodeo Championships in Boston; the Silver Spur prize at the Gladewater Round-up Rodeo for most sportsmanlike competitor; the Crawfish belt buckle for best LA cowboy; and the prize for top cowboy in Oklahoma and Arkansas. He was the first professional cowboy from Louisiana and the first Louisiana PRCA cowboy to participate in the National Finals Rodeo in Dallas.

T. B. was a national celebrity not only for his rodeo wins but also for his Wrangler advertisements in the early 1950s. He was a natural for the Wrangler contract: he was a classy-looking cowboy in his starched white shirts and, always, Wrangler jeans. For a year a picture of T. B. was slipped into every pair of Wrangler jeans that left the factory.

T. B.’s first wife, Dorothy, was hit by multiple sclerosis in the 1960s. T. B. gave up rodeo competitions in the 1970s to stay home and take care of her until her death in l982. Their daughter Judy Weisgerber wrote in 2001 that “love for family was high on our list of priorities, but only after our love and respect for God. My two sisters, brother and I learned to respect other people, their animals and their material possessions…Working alongside three generations on the farm also instilled in each of us the importance of a strong work ethic.”

Porter has spent his life working hard and volunteering often. After his rodeo days, he kept busy by operating a western store in Leesville and a trucking business that moved everything from garbage to houses, and by driving a school bus. He has served as Chairman of the Livestock Advisory Committee of the Farm Bureau Board, President of the Vernon Parish Cattlemen’s Association, and President of the Louisiana Cattlemen Association. He joined the Leesville Lions Club in 1951, served as President, and is now the oldest member. He was Chairman of the Leesville Lions Club PRCA Rodeo and was responsible for the rodeo being sanctioned by the PRCA. He was a board member of the Cowboy Hall of Fame in Oklahoma City and was a member of the Louisiana Department of Agriculture Sanitary Board.

T.B. supported rodeo by helping young people learn the skills of calf roping and bulldogging. Porter Ranch has had a practice arena for rodeo education for over 60 years. His own children and grandchildren have been successful rodeo competitors at state and national levels.

Nowadays the traditions of Porter Ranch continue with the help of T. B.’s son David. T.B.’s daughters drop in to help out, as well. But T. B., at 85, is the motor behind the ranch. His daughter Judy describes his battle with the bulldozer:

“Around 2 p.m. [on March 2, 2012] he went to jump start the bulldozer to work on the road that was muddy and hard to drive through. The bulldozer started, and he went to climb off to back up his truck. He put the dozer in neutral and when he stepped on the track, the dozer jumped in reverse. This threw him down and the dozer track ran over his right arm. The arm was broken above and below the elbow. His right shoulder was pulled out of place, the right collarbone and right shoulder blade broken, and the muscle between the shoulder and elbow badly injured. He tried to call David [who was pressure-washing a dump trailer] and David did not hear the phone. Daddy got up and put his 5-speed truck in reverse, backed up, put it in drive, and drove to the shop where David was working, about 100 yards. He told David that he was hurt and hurt bad and needed to go to the hospital. He made sure David turned everything off before leaving. He never lost consciousness and was fully coherent until surgery around 7 p.m. that night. He turned 85, March 9, in the hospital…” When he was finally discharged, says Judy, “the best medicine was to be able to drive through the pastures and check on his cows.” A tough cowboy indeed.