Written by Barbara Newtown

Original Publish Date June 2014

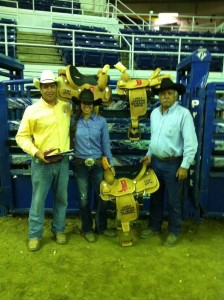

I’m sitting in the stands at the Louisiana High School Rodeo Finals at the Burton Coliseum in Lake Charles, Louisiana. It’s time for Mia Manzanares’ goat-tying run. Her horse is fast and straight, her dismount is swift and clean, and she grabs and trusses the goat before he knows what hits him. I am impressed by Mia’s eyes. She focusses forward with total commitment. Her technique and passion pay off: half an hour later she is taking her go-round victory gallop. Mia ends up winning all three go-rounds in goat-tying and qualifies to compete at the National High School Finals Rodeo. Later I learn that Mia’s brother Micah has qualified for the Junior High Nationals with his chute-dogging skills.

The Manzanares family invited me to their “compound” in Opelousas, Louisiana, a few weeks before the state rodeo finals. Kiko Manzanares and his wife Joann; their son Pancho, his wife Kathryn, and their children Mia, Micah, and Emma; and Kiko and Joann’s daughter Juanita, her husband Todd Broussard, and their son Blaise all have homes off a main driveway. The drive ends near a level and generous arena, complete with cattle-handling chutes at one end.

I show up at their backyard arena in time for after-school rodeo practice. Kiko, Joann, Juanita, Todd, and I watch from the fence as Mia, Emma, and Blaise work on their rodeo skills. I witness what happens when commitment to a sport and love of family unite.

“We do this every day after school and work,” says Kiko, as we watch Mia’s little sister Emma gather her rope and aim her loop again at her calf. Emma sits in the saddle with quiet legs and a supple back. Her seat is secure and balanced, which allows her to concentrate on her throwing. Kiko doesn’t yell advice; he lets his granddaughter work out the angles and speeds herself. “She’s coming along,” Kiko says quietly.

Mia and her cousin Blaise sort some steers and Blaise gets ready to practice bulldogging. To my uninitiated eye, bulldogging looks like a burst of uncontrolled speed from the steer and the horse and rider, followed by a superhuman effort to throw the steer. Kiko says that Blaise is working on making sure his horse waits until the steer has gotten a head start. In fact, his horse gets a little too eager, and Blaise lets two steers burst out of the gate while he holds his horse back. Getting to run away scot free is good for the steers, too; it keeps them from getting sour. Kiko tells me that bulldogging, which requires jumping off a galloping horse, is a high school event. The junior high sport of chute dogging is done on foot.

Kiko also explains that Blaise is not trying to bring down his steer with sheer force. “You pull the steer to the left, and his momentum helps you throw him.”

Kathryn, mother of Mia, Micah, and Emma, gets home from work and comes over to the arena to watch. Her husband Pancho is a pilot for a private company that flies executives all around the world; he is in the Mideast this afternoon. Pancho later tells me that he used to compete in team roping and steer wrestling, but now he concentrates on helping his children achieve their own goals. His wife Kathryn wasn’t raised in the rodeo tradition, but, as Pancho says, “we’ve had twenty years to indoctrinate her.”

When Blaise finishes with his last steer, the family works together to put up the horses, let the calves and steers back into their pasture, and pick manure out of the arena. I notice Blaise’s cowboy boots: they are wrapped around and around with duct tape.

When Blaise finishes with his last steer, the family works together to put up the horses, let the calves and steers back into their pasture, and pick manure out of the arena. I notice Blaise’s cowboy boots: they are wrapped around and around with duct tape.

“Those boots look ready for the recycle bin,” I say.

“Steer wrestling is hard on boot heels,” says Blaise. “I don’t wear my good boots for practice!”

I hitch a ride in the family golf cart across an expansive lawn to the home of Mia’s Aunt Juanita. Her husband Todd Broussard shows me his leather workroom. He creates tooled belts and knife scabbards that are becoming famous around rodeos. “The best advertising is having someone walk around a rodeo wearing one of my belts,” he says. He shows me a gorgeous custom belt that celebrates the owner’s biggest rodeo wins.

Inside we all sit down for coffee and conversation. I want to know more about Kiko, the elder statesman of this remarkable family.

“I’m from New Mexico,” says Kiko. “My grandfather was the sheriff and the chairman of the Democratic Party of Rio Arriba County. He had six children.” Juanita says that her great-grandfather expected all his sons to go into politics, and he expected his daughter to go into a nunnery to get a formal education.

“My dad was a rancher, not a politician,” says Kiko. “We had a few head of cattle and some sheep. We irrigated and made hay. My parents had four boys and a girl, and I was the second oldest. My sister became a nun and a teacher, my oldest brother became a politician, my next brother worked for the Bureau of Land Management in charge of dams and waterways, and my youngest brother became a teacher and a state champion basketball coach.” Kiko says that his father was proud of the accomplishments of his kids.

Kiko had two uncles who lived and worked in Washington, D. C., and who believed that Kiko needed to see the wider world and to get a taste of politics. They arranged for Kiko to come live with them and become a Congressional page. Kiko went off to our nation’s capital…at age thirteen. Nowadays, the congressional page posting is awarded to students of college age.

“I was sponsored by the late Congressman John J. Dempsey from New Mexico,” says Kiko. “He owed my grandfather a favor because of my grandfather’s support. Then I worked for Senator Chavez and Congressman Fernandez from New Mexico. I got to meet John F. Kennedy when he was a senator. I worked at the House of Representatives for 2 ½ years.

“So they sent me to Washington, D. C., without even asking me if I wanted to go. I got on the plane in Albuquerque and had a layover in Kansas City while they serviced the plane. I came down the ramp. The other passengers went into the terminal to wait, but I stood at the foot of that ramp, holding onto the handrail chain, for the whole layover— because I was too scared to let go and maybe miss the flight. All I know is, when they sent me over there to Washington, I had never seen a streetcar, I had never seen a taxicab, I had never seen a bus or an airplane, I had seen zero! ”

Being a page was grueling for any youngster. The pages attended school at the Library of Congress from 5 AM until 9:45 AM, and then had fifteen minutes to get to the House to start their day. When Congress had filibusters and stayed in session until midnight or later, the pages had to sit quietly in the chamber the whole time. Afterwards they still had to do their homework and be ready for the next morning of school. And they had to maintain a B average. Sitting all day was especially hard for Kiko, who had grown up hunting and fishing and riding his horse in the mountains, whenever he wanted, without supervision.

“It was a wonderful experience, going to Washington,” says Kiko. “But it was something I wouldn’t put my own kids through, at that age. No way.”

For the rest of his life Kiko hasn’t had a scrap of curiosity about what he might be missing in the cities. He was glad to return to New Mexico and get back to the ranch. He took up bull riding and bronc riding, and when he became a father he turned to calf roping. He has become a teacher of rodeo skills to his children and grandchildren.

When Kiko came of age, he joined the Army. While he was stationed at Fort Polk, he would drive 93 miles to Opelousas for R and R, because Fort Polk was in a dry parish. He met his future wife, Joann, at a dance. Kiko and Joann moved back to the little town in New Mexico.

“I moved to Louisiana in 1969, because my father-in-law asked me if I would come work for him, doing farming. He said if I liked farming we could go in partnership.” Joann’s father didn’t have a son, so he was pleased when Kiko said he would buy into the business. “We farmed together until Joann’s father retired. Then I bought his other half and went on my own until 1998.” Kiko and his son Pancho now own about eighty acres, where their homes and arena are located, but Kiko used to farm not only the land from Joann’s family but almost a thousand acres of other people’s land. “Cash farming,” says Kiko. “I would pay the owner to rent his land, and I would keep whatever I could make.”

Kiko is living an interesting dream: he is surrounded by his family, “his chickens.” He says that he loves what he is doing—being a rodeo mentor to his grandchildren—and he’s going to keep doing it. “We practice every day that we can in the arena, and we try to be the best that we can be. If they beat us, they beat us, but it isn’t because we haven’t tried.”

Mia speaks up. “We practice because we enjoy it, but also because we want to win.” Kiko agrees, and says, “I enjoy doing it because I love rodeo, and have always loved rodeo, but I do want to win.” He adds, “After a bad run, I’ll come back to the roping pen and try to find out what went wrong and what we could do better.”

I ask Mia if she ever felt pushed. “But you need that push,” she says. I am so glad they pushed me. My family wants me to be the best that I can be and I push myself.”

Blaise agrees. “Pushing is a necessity. You need the support of your family and friends. Without it, you fall through the cracks.” Blaise points out that the discipline of training for rodeo and taking care of the animals helps with time management skills.

Mia says, “I’m out in the arena instead of getting into trouble!”

I ask Blaise if bulldogging is easier if the human is tall and heavy. “Personally, I feel that body type is unimportant if you have good technique. I have a friend who must have been no more than four feet tall when he started steer wrestling in high school. And he could throw a steer.”

Blaise’s father Todd explains the technique to me. “You aren’t really slowing the steer down by digging your heels in the dirt. You’re trying to shape the steer. Then you’re pushing down on the tip of the left horn with your left hand and bringing his right horn up with your right hand. His body will follow his head.”

Blaise says, “If you use brute strength, you’ll get hurt.”

“Strength plus technique is good,” says his dad. Blaise tells me that he does do strength training. Mia does a lot of cardio: she runs at least three or four miles a day. “I also do legs and abs, and I play soccer and softball.”

Kiko reclines in his chair and listens with quiet pleasure as his grandchildren talk back and forth about rodeo. His wife Joann and his daughter Juanita are busy in the kitchen. Behind him there is a long rack loaded with trophy saddles. In front of the sofa where I’m sitting, a coffee table with a glass top displays an array of shiny belt buckles. Kiko looks truly contented.

Kiko says, “I am seventy-three years old, and I have no regrets about how I have spent my life. It’s been a good ride.”